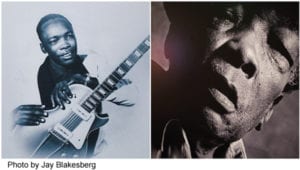

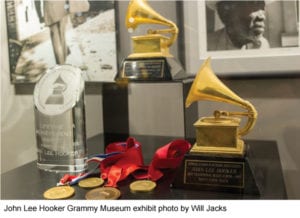

John Lee Hooker would have been 100 years old in 2017, and the landmark is being celebrated with a new spectacular 5-CD boxset, King Of The Boogie, and an exhibition at the Grammy Museum in Cleveland, Mississippi (through February 2018) before it moves to the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles.

This is the sort of thing the music industry does regularly, of course, but a legendary bluesman such as John Lee Hooker really does warrant such a treatment. In the blues, where even aficionados will admit there’s a lot of music and artists that sounds similar, John Lee was a truly remarkable one-off. King Of The Boogie boxset producer Mason Williams says, “Even at 100 songs, this set is just a snapshot of John Lee Hooker’s incredible and influential career.”

This expansive “snapshot” takes the listener on a long journey he took from Hooker’s early days in Detroit, to his time in Chicago recording for Vee-Jay Records and up through his later collaborations with Eric Clapton, George Thorogood, Van Morrison, Bonnie Raitt and Santana, among others.

“The Deepest Blues That Ever Was”

You’ll rarely find John Lee Hooker’s music transcribed in guitar magazines or websites. Why? There’s little point in trying to copy him. The best you can do with Hooker’s music is to feel it. He would often play 13 bars in what was theoretically a supposedly standard 12-bar blues. His solos stabbed like shouts, he would speed up songs mid-way. He knew little about keys of songs.

In a rare 1995 interview with The Guitar Magazine, Hooker admitted: “I don’t like to play a song the same way as everybody else. I can do. But I don’t want to.”

Ronnie Wood remembers when The Rolling Stones toured with Hooker in ’89, one of the blueman’s biggest but significant outings. “We never had any clue what key he’d be playing in,” Wood told Rolling Stone. “He’d look at us and say, ‘What key?’ He had no idea. Finally, before one song on the second night, he said “E” and I shouted to the band, “Boys, he gave us a clue! It’s in E!”

There are some who say they’ve learned from John Lee’s records, though. George Thorogood, who’s made Hooker’s “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer” something of his own signature song, recalled how Hooker albums Moanin’ And Stompin’ and Alone “were really strong records in terms of my learning how to play the guitar.

Thorogood told Musicaficionado.com, “Like Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker was playing alone, unaccompanied, so he made a lot of music all by himself. That encouraged me in thinking that I just might be able to pull this off, because I wasn’t having a lot of luck with bands. I played these two albums over and over again. They were really important to me when I was comin’ up and figuring things out.”

But for a lot of other players, John Lee Hooker’s primal boogie is almost otherworldly. Charles Shaar Murray, award-winning author of the JLH biography Boogie Man, tells Gibson.com: “John Lee Hooker was a musical primitive in the highest sense of the term. He cut ‘Boogie Chillen’ in 1948, but his music sounded older than that of musicians who began their recording careers a quarter-century earlier. He played what Charlie Musselwhite called ‘the deepest blues that ever was’… but Pete Townshend credited him with the invention of the power-chord.

“John Lee Hooker’s music was more than just ‘the blues’: it sounded like the raw stuff from which the blues was originally formed.”

John Lee Hooker was introduced to music by his stepfather, Delta bluesman Will Moore. “He played guitar, too,” Hooker recalled. “I checked out electrified [guitar] in the ’50s but it wasn’t ’til ‘Boom Boom’… that’s when I really stretched out on the electric.”

It was another Gibson-playing blues great, T-Bone Walker, who gave Hooker his first electric guitar, an Epiphone. “I was already established but not electrified. I still have that old Epiphone that T-Bone laid on me back in Detroit… Playin’ music, I really got into it big when I hit Detroit,” he said.

“A lot of work was goin’ on… wartime, World War II and the factories were goin’ and every city was boomin’. Detroit was boomin’.”

Hooker’s unique style itself may have been due to his initial settling in Detroit rather than Chicago. As Hooker once told blues writer Jas Obrecht (who also contributes to the booklet of King Of The Boogie): “Too much competition there [Chicago]. Too many blues singers was there. I wanted to go to Detroit where there wasn’t no competition between blues singers. I went there, and that’s where I grew up. I never lived in Chicago.”

In four years, from 1949 to 1953, Hooker made scores of albums for 24 different labels. He’d famously just turn up and record. He didn’t make much money, but he always liked the finer things in life, from his sharp suits to guitars. In a famous publicity photo for Modern Records in 1952, Hooker posed with an early Gibson Les Paul Goldtop with trapeze tailpiece: “one of the first ones,” he remembered. “It was beautiful. Beautiful.”

As with many of the incredible blues artists of the mid-20th century, it took the 1960s blues revival to really shine a spotlight on Hooker. In the U.K., Hooker became a cult hero: The Rolling Stones and The Yardbirds were disciples. Moving onto the 70s, his boogie style was soaked up by numerous by rock’n’roll bands of the day, notably Canned Heat (seek out the collaborative Hooker ‘N Heat LP) and ZZ Top, whose “La Grange” is almost a John Lee homage.

“With John Lee, there’s a break in the continuity of styles,” Rolling Stone Keith Richards, a lifelong fan who guested on Hooker’s album Mr Lucky, told Jas Obrecht. “What he picked up has got to come from one generation further back than anybody else, and John Lee can still make it work.” Even in more recent times, the likes of The Black Keys exhibit a huge debt to John Lee.

Hooker’s Guitar Style

Hooker remained faithful to Epiphone and Gibson guitars for most of his professional life, a favorite model being the Epiphone Sheraton – Epiphone introduced a signature John Lee Hooker Sheraton and Sheraton II in 2000, the year before his death. But he was also a regular player of the similarly-built Gibson ES-335.

Hooker didn’t use a pick, utilizing his thumb to hit the bass notes and brushing his lead licks with an upstroke of his index finger. Much of Hooker’s playing was in open G, which he first employed for his 1949 recording of “Crawlin’ Kingsnake”(covered by The Doors), and he also regularly capo’d at the second fret to play in the higher-toned open A, and at the fourth fret to play in open B (listen to the chiming brightness of 1949’s “Hoogie Boogie”). But he also played in standard tuning, a relative sophistication for pioneer bluesmen.

“He was astonishingly sophisticated,” argues Charles Shaar Murray. “If other musicians were prepared to travel with him, and be guided by him, through his own musical universe, he could – and, during a career lasting over half a century, indeed did – perform with jazz, soul and rock musicians as well as those versed in the blues.”

Hooker’s mantric grooves aren’t to every guitarists tastes. His playing is a world away from the distorted neo-shred that “electric blues” morphed into in the 70s. But that’s okay: Hooker’s blues always tapped a deeper vein.

As Charles Shaar Murray concludes: “Hooker was both the grandest of grand archetypes of the blues, and an artist unlike all others. He was the original Boogie Man: gone in the flesh, immortal and omnipresent in spirit.”

Simultaneously long gone yet also 100 years old, John Lee Hooker’s still here.

Contact Conner for Gibson questions or availability

Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge Click to Enlarge

Click to Enlarge